My father attended church with us only twice a year, Christmas and Easter. Mother went more regularly until we were older, at which point the car barely came to a full stop before she started shooing us out the door.

“Meet me right here when church is over!”, she shouted as she accelerated past the crosswalk.

There was always a line of people waiting to enter the sanctuary. Dark-suited, older, white males stood solemnly, just outside two sets of double doors, holding small stacks of church bulletins which I had came to think of as my ticket; Admit One. As my sisters and I waited our turn in line, I studied the ushers. They always put me more in mind of sentries guarding a castle than greeters for the “House of God”.

Standing in that line was a bit like walking downtown sidewalks surrounded by sparkling skyscrapers of varying heights. The air lay thick with a potpourri of scents spritzed from cut-glass atomizers, as I shuffled my feet inside black patent leather. Women, who had soldiered through the previous week in their uniform of polyester pants and rubber-soled, terry-cloth scuffs, now fanned their tails like so many peacocks in designer finery. I studied the mink stole draping the shoulders of the woman in front of me, appreciating the varying hues of brown, gold, and black while following the seams connecting the pelts with my eyes.

“Love the dress!” The furred woman spoke to another woman just to the right of us whose eyes sparkled above her rouged cheeks before looking down at her dress, as though she had forgotten what she was wearing.

“Oh, thank you!” Her hands went to her bare arms and I felt her self-consciousness. “What a gorgeous fur! Is it mink?”, she asked through strained painted lips.

“Yes, Gordon brought it back from his last trip to New York.” Red-tipped nails caressed both arms. “I wore it today since it might be my last opportunity before summer.”

“Gayle! Is that a new ring?” Another feminine voice swiveled my head to the left, just as the older woman next to me retrieved her hand from its spot under her husband’s arm.

“Yes! Robert gave it to me for Christmas.”, she said, flashing a smile at her benefactor, who answered with one of his own. She raised her hand towards her friend who turned it this way and that, in appreciation.

“Wow! Pretty snazzy, Robert. Gayle must have been a good girl!” Gayle lost her footing in laughter, bringing the tip of her pointed-toed pump firmly against my Mary Jane. I turned swiftly so as not to be caught staring. By the time I reached the sentries, the aisle separating the pews looked more like a catwalk.

If most Sundays produced a fashion show, Easter Sunday served as “Fashion Week”. No one was immune. Men bought new suits, and corsages for their ladies. Women scanned racks for weeks, in search of the perfect dress and dyed new pumps to match, before retrieving their jewelry from velvet beds inside safe deposit boxes.

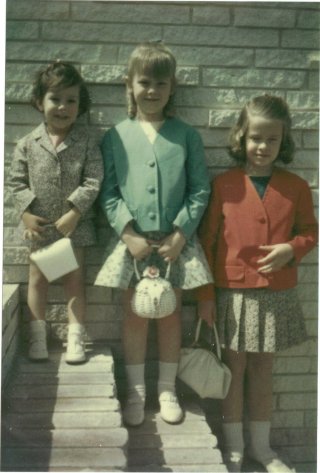

Girls were taken shopping for Easter dresses. Most girls. My sisters and I were taken instead to “Cloth World”, where we were encouraged to choose from one of several fabrics from which my mother would fashion a suit. The fabrics were coordinated so that each girl would wear a solid and a print, and the style would vary, if only slightly.

My mother was an excellent seamstress, having culled the talent from her mother who made her living as a tailor in an exclusive men’s clothing store. She made most of our clothes and some of her own. One of my fondest memories involves a church fashion show, for which my mother created four identical white dresses; one for her, and one for each of us. Walking as ducks in a row, we took the stage together the afternoon of the show. I don’t remember who actually won, and it never was important. In my mind, my mother stole the show.

As a child, I never appreciated our carefully coordinated Easter suits. I felt dowdy and out of fashion. I watched other girls swish by in taffeta, and lace and wished the sewing machine had never been made available for purchase by the public. And, I resented my mother for not understanding.

Several years ago my grandmother died, leaving behind boxes and boxes of photographs my mother had sent her in celebration of our childhood. My youngest sister, who had been my grandmother’s primary caretaker, arranged a luncheon at which she invited us to open the boxes and take the pictures that meant the most to us. As we leafed through the photographs, there were countless images of my sisters and me, usually backed up against a wall and standing in descending order, wearing our mother’s handiwork. When I searched my mind today, for Easter memories, these pictures were the first thing that came to mind.

We miss so much when we are children, when our minds are not yet fully formed and ready to understand the importance of things. As I study the photographs now, I see more than meticulous construction and careful coordination. Forty-plus years later, I see time, and effort, and sacrifice, and love. And, in her sharing of the photographs, I interpret pride; pride in her children, yes, and something more. By sending these photographs to her mother she shared, and appreciated, her legacy.

I hope I said it then. I wish she could hear it now.

Thanks, Mom.

© Copyright 2007-2009 Stacye Carroll All Rights Reserved