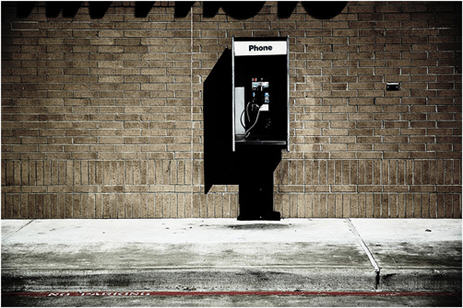

The telephone had yet to be connected in our apartment, prompting my roommate and I to stop at a local convenience store featuring a bright-blue payphone on an outside wall. I had been in Athens just a couple of days, and I knew my parents would worry.

“Dad!”, I exuded. “It is so cool here! They have these little tin houses that look just like boxes, and people live in them!”

“There is a reason you’ve never seen those before.” The tone of his voice invited no further query, and it wasn’t long before I uncovered the stigma attached to those living in what I came to learn were “mobile” homes. Both of my parents had always described apartment dwellers as “itinerants”. As I reasoned the significance of the usually rusted metal hitch sprouting from one side of each of the carefully aligned boxes, I could only imagine how the people residing inside might be described.

Prejudice, fear, and an emphasis on keeping up appearances had proved a remarkably effective shelter.

Shortly after I married, and before I discovered my husband’s addictions, we spent many Sunday afternoons driving around town before heading out into the countryside. Gasoline was cheap then, and we had money for little else. As we headed back into town after a long afternoon spent cruising down country lanes, he asked if I minded if he stopped at a friend’s house on the way home. Several hundred feet after turning off the main road, I saw another form of box-shaped building; row upon row of brick encased boxes with tiny yards featuring an occasional patch of green that passed for grass. Each box looked exactly the same, down to the rusted, ripped screen door that hung tongue-like from its frame.

Ricky steered his prized vintage Cougar into one of the short cement drives.

“I’ll be right back.” The car shook with the force it took to close the extra-long car door. I looked around as I waited, and wondered at the plainness of my surroundings. Except for the occasional hardwood, there was little in the way of greenery, as though nothing would grow in this environment. Crowds of young adults congregated on various corners seemingly oblivious to the squealing children darting between their legs. Many people walked along the streets, calling my attention to driveways inhabited only by rusted tricycles and aged basketball goals that appeared to have sprung from the cracked concrete beneath them.

My husband emerged followed by his friend, a tall, thin African-American man with an amiable face. Ricky grunted with the extra effort required to open the antique car door before introducing him.

“This is Boysie.” He waved his free hand in the direction of the taller man’s smile.

“How ya doin’?” Boysie’s smile grew wider as he spoke, bending at the middle in an effort to see inside our small car.

The two men conversed for several minutes before Ricky slid into the driver’s seat with a “See you, man.”, and the engine roared to life.

As we headed back the way we had come I wondered what my parents would think if they knew I had visited “The Projects”; and, at night! It never occurred to me to wonder what we were doing there. I had no frame of reference. Months would pass before I realized Boysie was my husband’s dealer.

Later, long after I had come to terms with, and rectified, the mistake I’d made in marrying a man I hardly knew, I went to work managing a midwifery practice that served mothers without insurance. Some of the women were Boysie’s neighbors, and many of those that didn’t live in a housing project were on a waiting list.

It was my job to screen patients for eligibility. Lack of insurance was just one requirement. Income and family size were also considered. Most of the women were already receiving government benefits that, at the time, grew with each successive birth. A woman who knew how to work the system might receive child support from more than one man, food stamps, Medicaid for herself and her children, WIC (another government supported nutritional program), and free or nearly free housing. It was no wonder that, very often, the clothes worn by the woman I was interviewing were much more stylish, and expensive, than mine. The benefits paid by our government to women who knew how to work the system gave a whole new meaning to “expendable income”. And who could blame them? In most cases, they had been raised in the same environment, just had their mothers before them. And, it was so easy…

It was my job to screen patients for eligibility. Lack of insurance was just one requirement. Income and family size were also considered. Most of the women were already receiving government benefits that, at the time, grew with each successive birth. A woman who knew how to work the system might receive child support from more than one man, food stamps, Medicaid for herself and her children, WIC (another government supported nutritional program), and free or nearly free housing. It was no wonder that, very often, the clothes worn by the woman I was interviewing were much more stylish, and expensive, than mine. The benefits paid by our government to women who knew how to work the system gave a whole new meaning to “expendable income”. And who could blame them? In most cases, they had been raised in the same environment, just had their mothers before them. And, it was so easy…

Occasionally, I counseled a woman struggling to support her family on minimum wage. Ironically, the pittance she brought home as a reward for dirtying her hands doing a job most wouldn’t even consider, left her ineligible for assistance of any kind, and usually these women, too, joined the welfare rolls months before thier babies were born. Very soon, I came to think of this situation as “government induced poverty”.

During this time, the Olympic Games were held in Atlanta, and Athens was to host some of the competitions. Much was said about the state of public housing in the area, and the need to clean up before the world came to visit. I was heartened to think that some of our patients’ homes would be receiving much needed repairs, until I realized that the plan was to erect facades crafted of aluminum siding over the fronts of their homes. By the time the torch arrived, the ugly brick boxes had been transformed into quaintly crowded cottages. Flowers had been planted along the borders of newly laid sod. But inside, gaping holes marred many kitchen and bathroom floors in which rusted faucets dripped continuously. Unsightly window air-conditioning units had been removed, as had the rickety screen doors, leaving the inhabitants inside with no relief from ninety-degree heat. It seemed governments, too, were invested in keeping up appearances.

Last week, bulldozers razed the last remaining housing project in Atlanta. Upon hearing this, my first thought was of the residents. Had they been provided for? Did they have homes? Where did they go? It seemed like a heartless act perpetrated on a helpless population.

Upon reading an article in the local paper, I learned that, in 1936, Atlanta was the first city in the nation to erect public housing. I know a lot about my city. Somehow, this inauspicious fact had escaped me. The article went on to suggest that Atlanta is now the first city in the nation to abolish public housing. I continued to read, in hopes that a solution had been offered, and learned that displaced families will receive twenty-seven months of various types of assistance, with a goal towards self-sufficiency.

Further down the page the housing authority’s executive director was quoted as saying that the demolition “marks the end of an era where warehousing families in concentrated poverty will cease.”

Every now and then, we get it right.

© Copyright 2007-2009 Stacye Carroll All Rights Reserved