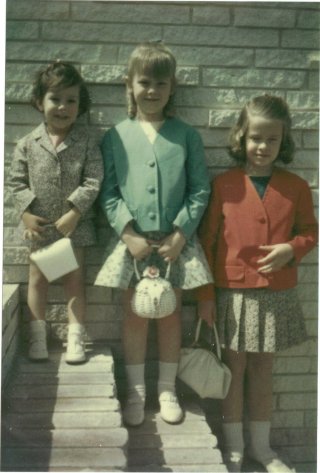

My father fathered four females.

I am the eldest.

“My name is Stacye, and I’m a Daddy’s Girl.”

Of course I am. We all are. We have a Daddy…we are girls. And, like all good southern girls, we actually call him “Daddy”.

Addressing him that way comes naturally. Admitting to it conjures images of Orson Welles, syrup dripping from the corners of Joanne Woodward’s unlined mouth, and a discomfort that smells like warm gardenias.

By now, you have an image. My blonde hair is long, as are my legs. My eyes are large, and probably blue. There’s a natural curve to my lips, which are carefully painted pink; never red. And, you would be right.

Except, the image is that of my sister, my baby sister to be exact; the one who still throws her limbs on either side of his recliner as she sprawls across his lap, the one that bakes for him, calls him daily, and houses him when he leaves the crystal sands of his beloved beach for important family events, such as his birthday, Father’s Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas.

But I was there in the early days…

On Saturdays, we logged hours in his two-toned El Camino, driving around town doing errands. His “Honey-Do” list became our “Trip for Two” list, as we traversed suburban side-roads between the post office, hardware store, garden nursery, and occasionally, the local mechanic.

Mostly, we talked.

“Never forget who you are!” I especially loved that one. “You’re a Howell!”

He said as though it meant something. He said it as though mere mention of our name was enough to garner the respect of anyone within hearing distance. He said it so often that I believed it.

He told me stories of him and Joe Wiggins. It was always “Joe Wiggins”, never just “Joe”. Perhaps there was another Joe. I don’t know, he never said. But, he never mentioned his childhood friend without inserting his surname.

I remember the sun being particularly bright one Saturday afternoon. We’d probably just dropped my car off…again. The dilapidated shop occupied most of a block-long side road. They specialized in foreign “jobs”, such as Hondas, Toyotas, Datsuns, and Cortinas. They didn’t actually specialize in Cortinas. No one did. Because, no one east of the Atlantic drove one…except me.

“Why don’t you divorce her?’ My right hand swept blonde wisps from my face. The air conditioner in the El Camino had stopped working weeks ago.

“Because Howells don’t divorce.” He said it as though it were true. He said it as though he was raised by two loving parents instead of a crotchety grandmother who insisted he sweep their dirt floor each morning before mounting the newspaper-laden bicycle he later rode to school.

And I believed, because I didn’t know.

He taught me about cars. He didn’t change his own oil. He had “Eddie, The Mechanic” to do that. But, he taught me to change mine.

He lay under the car, while I leaned across the engine. We changed the oil, added water to the battery, and checked all the other fluids. When we were done; large, continent-shaped swatches of my flannel shirt were missing.

“Battery acid.”, he said while ordering me inside to change my shirt with just a look.

But I kept it. I kept the shirt. I even wore it a few times. Now, I’m sure it lies alongside my holey Peter Frampton t-shirt; the one I kept for almost twenty years before deciding that I really never would wear it again.

But I will…

Angels will sing, harps will play, and there I’ll be…Daddy’s Girl…wearing a holey flannel shirt over a faded Peter Frampton t-shirt.

“Do you feel like I do?”